The COVID-19 pandemic is a historic event that has galvanized inter-generational cohorts in the fight against a common enemy. I will not attempt to wax-poetic about the implications this will have on our way of life for when we inevitability get through to the other side of this pandemic, as there are much more qualified experts that can offer better educated opinions on the matter than I can. What I will attempt to do is explore a way to re-frame the implications of this health crisis for investors that are dealing with both emotional and financial stress as a result of the pandemic. The reaction in financial markets has been violent and swift; however, the most recent downturn may have a silver lining for investors. Portfolios that could have used a health check-up but were being neglected because of tax implications can now be undertaken. With financial markets still marred in a cloud of uncertainty, investors can use this opportunity to rebuild their portfolios with a focus on creating long-term robustness. The famous quote often misattributed to Winston Churchill, “never let a good crisis go to waste,” seems suitable for investment portfolios in this situation.

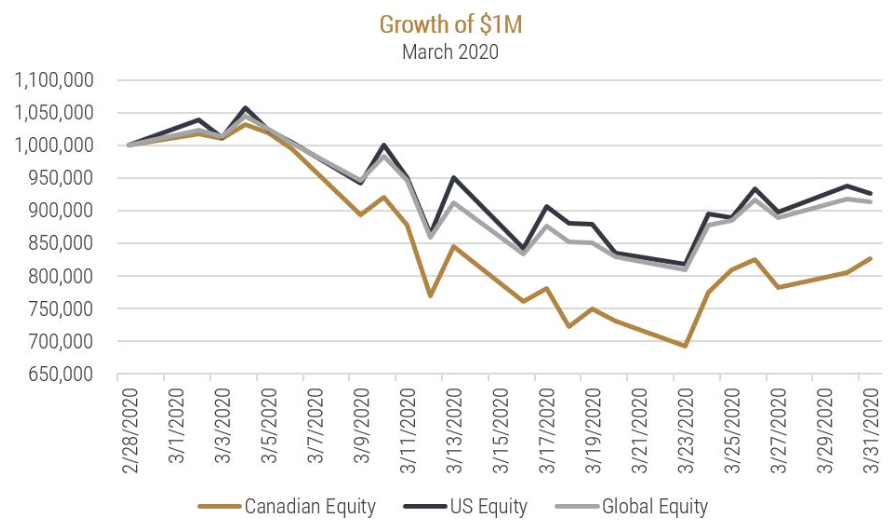

Geographic diversification is always an integral part of portfolio construction and is a timely topic to tackle for Canadian investors given the most recent string of events. Not only has the COVID-19 pandemic severely hampered consumer demand thereby pushing equity prices lower, but at the same time, Saudi Arabia ratcheted up oil production and crushed world oil prices. This double-pronged assault was catastrophic for Canadian equity investors, with the Canadian market dropping -17.4% (S&P TSX) for the month of March, much worse than the -7.4% of the U.S. equity market (S&P 500) and the -8.6% experienced for global equity markets (MSCI ACWI). (Data sourced from Bloomberg)

The implications are shockingly clear. Canadian investors, with concentrated equity positions in their home country, have felt the fallout from the recent decline in financial markets far more acutely than other market participants.

Home country bias refers to the tendency of investors to favour assets from their own country over those from other countries or regions of the world. This behaviour can be defined as the amount of deviation in an investor’s holdings of their home country relative to a diversified international portfolio allocation. An investor who displays no home country bias would hold a domestic asset exposure in their portfolio that equals the share of that home country’s market size (market capitalization) relative to the total world market.

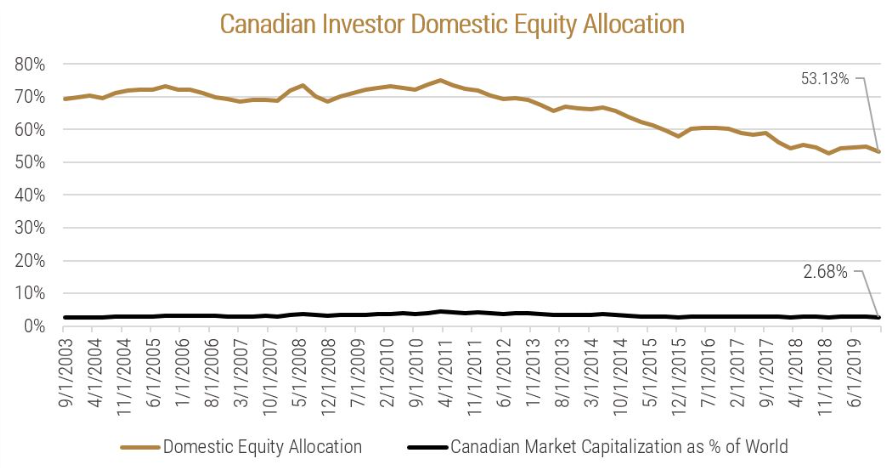

When examining the balance sheet of Canadian investors, the latest data from Statistics Canada shows that the domestic equity allocation of Canadian portfolios is roughly 53%. Yet, the Canadian equity market represents just under 3% of the world equity market capitalization.

While the allocation to domestic equities has ebbed lower in recent years (partially as a result from subpar Canadian market performance relative to the rest of the world), this still represents an extremely concentrated position in the Canadian market relative to its global weighting. The problem is further compounded by the fact that most Canadian investors live and work in Canada, so their employment income and real estate (assuming home ownership) are also tied to the fortunes of the Canadian economy.

To be clear, this is not a problem that is unique to Canadian investors. But, Canadian investors need to be cognizant of the potential issues when constructing their portfolios. All investors will have some sort of home country bias depending on the way they’ve structured their portfolio. The real question is: How much can the average Canadian portfolio be improved?

We would posit that one of the main reasons home country bias exists to the extent that it does is the perception of risk. While the improvement in technology and the creation of low-cost investment vehicles have allowed investors more affordable and efficient access to global markets, the movement toward a more globally diversified portfolio has been painfully slow. The assumption that investing outside of one’s home country introduces an increased risk profile is a misnomer – one that is easily dispelled when you dig into the data. The challenge is that “risk” is hard to quantify and means different things to different people. Without going down the rabbit hole on how we feel risk should be defined (we’ll leave that for another Insights piece), we will highlight that return profiles should be assessed in conjunction with the volatility of one’s portfolio – effectively, how stable the return profile of the portfolio is over time. The more stable the return profile, the easier it is for an investor to stick with their strategy when times are tough.

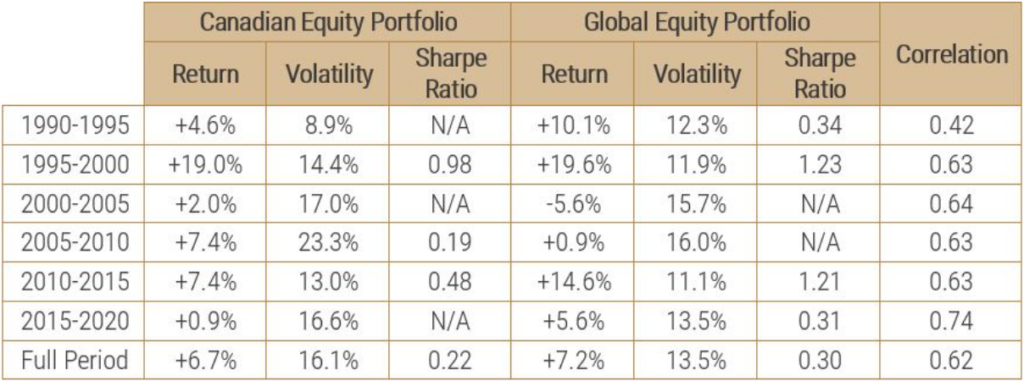

To begin our analysis of assessing portfolio robustness, let’s take a look at the difference in performance between a Canadian equity portfolio relative to that of a similar global equity portfolio. For the below analysis, I’ve compiled data going back to March of 1990 and examined performance over rolling five-year periods to capture different market environments. The returns of the global equity portfolio are denominated in Canadian dollars (i.e., no foreign currency hedging).

The above table illustrates that, outside of the decade from 2000 to 2010, global equities have outperformed Canadian equities with lower volatility. Part of the reason we see a lower volatility profile for the global equity portfolio is the effect of foreign currency exposure. The Canadian dollar is a pro-cyclical currency, which means when economic growth and risk assets are performing poorly, the loonie typically performs poorly as well. When the Canadian dollar weakens, this boosts returns of assets denominated in foreign currencies. Therefore, the exposure to foreign currencies in a global equity portfolio typically helps to insulate returns in times of financial market stress due to a weakening Canadian dollar. To avoid getting sidetracked, we will explore the topic of currency hedging for a globally diversified portfolio as part of a future Insights piece.

Outside of the performance and volatility differentials, the other interesting piece of data is the correlation between Canadian equity and a global equity portfolio coming in at 0.62. Modern Portfolio Theory states that when you have two asset classes which have positive expected return profiles and a correlation that is less than perfect, these assets can be combined to create a more robust portfolio.

Now let’s take a look at those same time periods but analyze a portfolio that has exposure to both Canadian equities and global equities. For this analysis, we will assume the exposure to Canadian equities is the allocation specified by Statistics Canada at the start of each measurement period. Though not on the previous chart, the average allocation to Canadian equity over the period is 66.4%.

As a Canadian investor, having some exposure to global equities has helped to lower volatility and improve return per unit of risk (Sharpe ratio) relative to a Canadian-centric portfolio. Canadian investors appear to be taking notice and have slowly been allocating more of their investment portfolio outside of Canada. But, at the current portfolio allocation of roughly 50% Canadian equity and 50% foreign equity, is this enough?

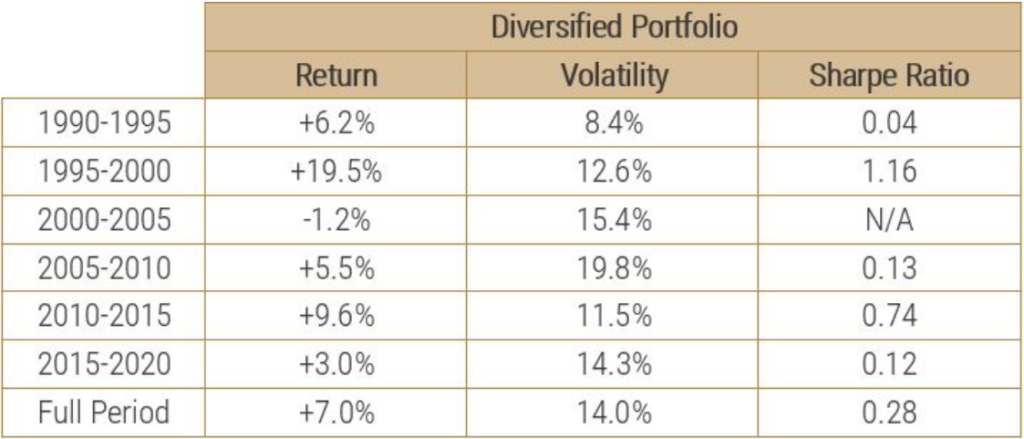

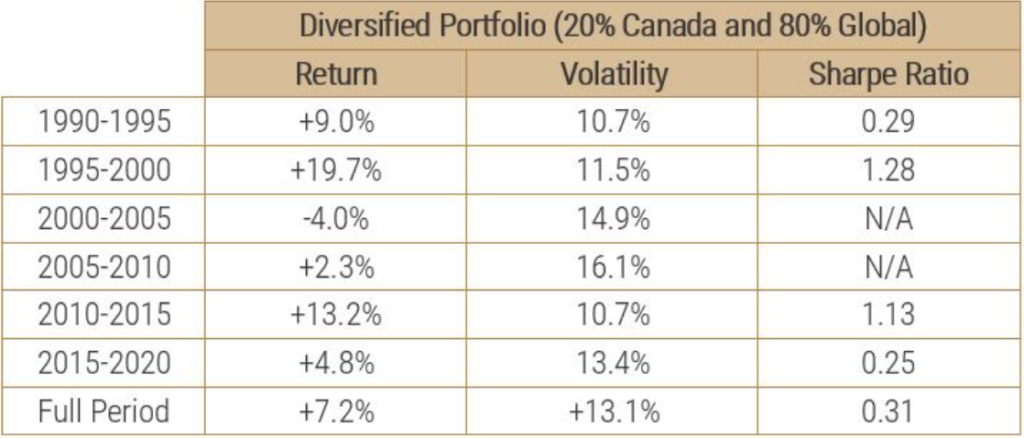

Understanding that there are reasons why a Canadian investor would want more domestic equity exposure than Canada’s market cap weighting (domestic liabilities, tax treatment on dividends, etc.) but realizing there are benefits to be gleaned by reducing home country bias, let’s look at this analysis one more time. The below table illustrates the risk and return characteristics of a diversified portfolio with a 20% allocation to Canadian stocks and an 80% allocation to global stocks.

When looking at the statistics for the full period, you may be thinking the benefit of further diversification doesn’t move the needle enough. By weighting more towards global equity, you get a modest annualized return bump and lower volatility, resulting in an improved Sharpe. For long-term asset allocators, this increased Sharpe is the holy grail. But, it’s understandable that for some it might seem like too much hassle when it doesn’t move the return needle by a large enough amount.

That is a fine argument if the collective “we” are all rational investors. The truth of the matter is that while we like to think we are all “long term,” at the end of the day, short-term volatility dampening has large implications for investor behaviour. If increasing diversification within a portfolio can help to smooth the variability of your return stream, it makes it that much easier to stick with your long-term plan and not bail when the seas get choppy. While some may point to the fact that March 2020 was a “black-swan” event that caught everyone by surprise and was a horrible month for most asset classes, this is precisely why we geographically diversify our portfolios. A monthly drawdown of -17.4% in Canadian equity markets gets just a little bit easier to stomach if you have exposure to an asset class that only declined -8.6%.

While this analysis doesn’t make the most recent downturn in financial markets any less painful, it may provide an opportunity to re-balance your portfolio so that it is less reliant on the Canadian economy – and being able to do so without footing a large tax bill is a bonus!

DISCLAIMER:

This blog and its contents are for informational purposes only. Information relating to investment approaches or individual investments should not be construed as advice or endorsement. Any views expressed in this blog were prepared based upon the information available at the time and are subject to change. All information is subject to possible correction. In no event shall Viewpoint Investment Partners Corporation be liable for any damages arising out of, or in any way connected with, the use or inability to use this blog appropriately.