While equity investors enjoyed another strong year of returns, the end of the year finished with a whimper as opposed to a bang. The Santa Clause rally never really materialized as equities chopped sideways throughout December, though with global equities posting a +18% gain on the year in USD terms, wishing for a continued equity rally may have been delusive. For bond investors, the holidays conjured images that bore a closer resemblance to Krampus than they did to Saint Nicholas. Not only did global bonds have another subpar year in 2024 by returning -1.7% in USD terms, but bond vigilantes continue to flash their teeth, pushing global bond yields higher. As we flip the calendar into 2025, the key focus for investors continues to be how the path of interest rates will evolve. The Federal Reserve (Fed) embarked on its rate-cutting cycle in September of 2024 and thus far has delivered 100 basis points of cuts to the overnight interest rate. Despite the Fed lowering the overnight interest rate, 10-year U.S. yields have risen from 3.6% to 4.7% over the same period, an increase of 110 basis points. Equities have held up reasonably well in the face of rising bond yields, returning +3.8% in USD terms over the period. The strength of the U.S. economy, consumer spending, and corporate earnings has helped to insulate equity returns over the period, though the elephant in the room is at what level long-term interest rates will start to weigh on economic growth and consumer sentiment.

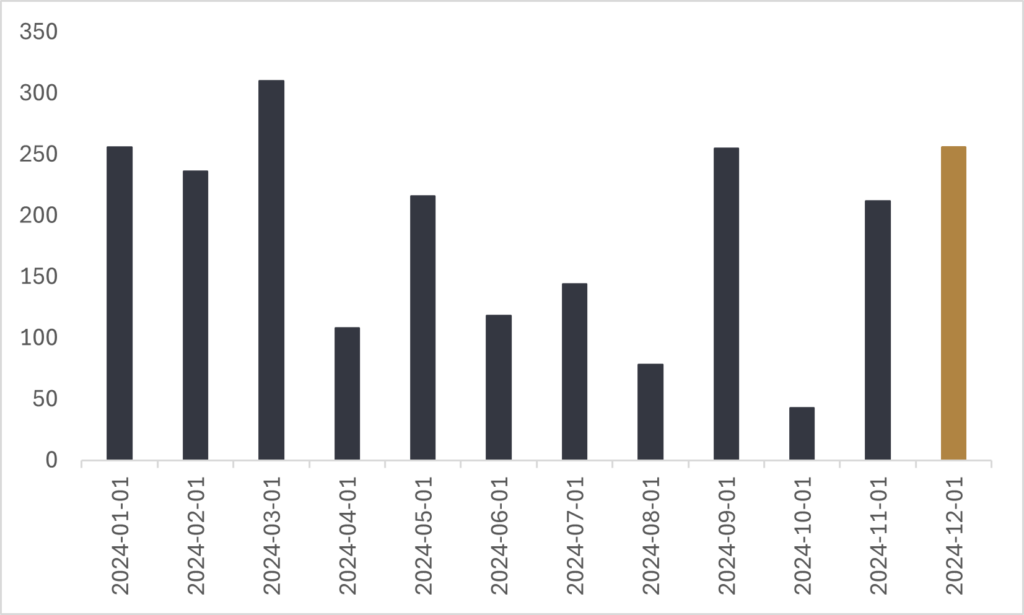

As investors returned from holidays, a raft of economic releases out of the U.S. added fuel to the yield bonfire. On Friday of last week, the U.S. economy created +256k new jobs for the month of December, blowing expectations out of the water. The unemployment rate fell from +4.2% to +4.1%, a reversal in the softening trend that we’ve been seeing in the labour market, which prompted the Fed to begin their rate cutting cycle. The December employment report showed that a rebound in the labour market hasn’t reignited wage pressure just yet, with average hourly earnings on a year-over-year basis slipping from +4.0% to +3.9% in December. The strong labour market wasn’t just unique to the U.S., with Canada also posting a stronger-than-anticipated rise in hiring with +90.9k new jobs created—the bulk of which was full-time employment.

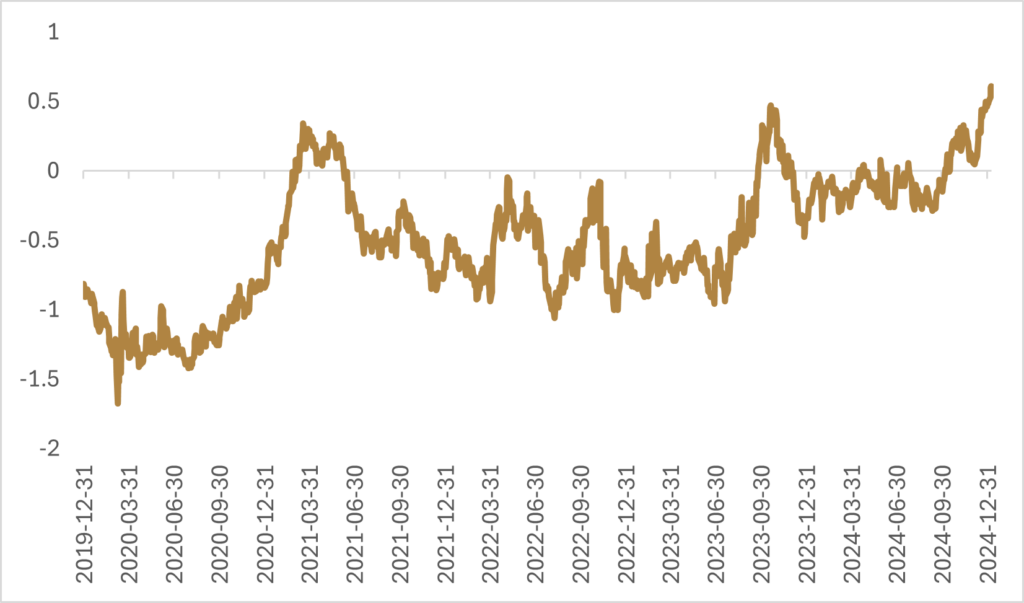

In addition to a firming labour market, inflation expectations have also turned higher, with the University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index showing consumers are anticipating prices to rise +3.3% over the next year, which is up from the median response of +2.8% in the December survey. Because inflation expectations can influence actual inflation due to the reinforcing feedback loop that expectations have on consumer behaviour, the sharp rise will be somewhat of an unwelcome development for the Fed and their quest to keep inflation (and inflation expectations) well anchored. What was quite interesting about the latest survey from the University of Michigan was the differences in inflation expectations based on political affiliation. Figure 2 does a great job of highlighting the stark differences in political affiliation and the ramifications on economic sentiment due to the election cycle in the U.S.

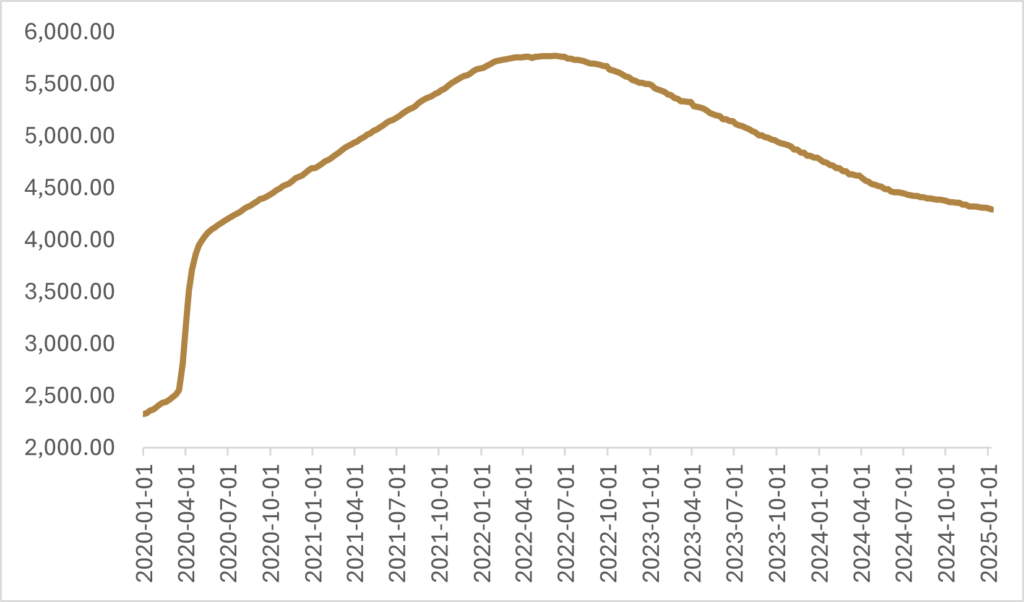

So even though the Fed has cut short-term interest rates by 100 basis points, the continued strength of the U.S. economy has adjusted the market expectations for where interest rates will land at the end of this rate-cutting cycle. When the Fed delivered their first rate cut of 50 basis points last September, market participants were anticipating that the overnight interest rate would eventually settle at 3%. However, with the better-than-anticipated economic activity and the potential for a resurgence in inflation, market participants are now expecting the Fed will only cut interest rates once in 2025, and the terminal rate will settle at 4%, an increase in terminal rate expectations of 100 basis points over the last four months.

In conjunction with markets anticipating a higher terminal overnight interest rate, the shape of the yield curve has also gotten steeper since September of last year. A steepening yield curve has implications for the real economy, as rising long-term yields can affect everything from mortgage rates and corporate borrowing, to commercial real estate. Part of this steepening is that the Fed has been cutting the overnight rate, which only affects the front-end of the curve, while at the same time the market is demanding additional premium to hold longer-term bonds through what is known as the “term premium.” The increased premium investors are demanding for holding longer-term debt is the result of investor uncertainty around the state of the fiscal deficit position in the U.S., as investors are not optimistic that there will be meaningful progression on reigning in the budget deficit from the incoming U.S. administration. At the same time, there has been talk from the newly nominated Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent about lengthening the duration of U.S. government debt, and markets are likely preparing for increased issuance further out on the curve. With the Fed stepping back from their U.S. treasury purchases as part of their balance sheet runoff and quantitative tightening, the pool of price insensitive buyers is decreasing, and the remaining price sensitive buyers are demanding increased premium to hold longer-date debt.

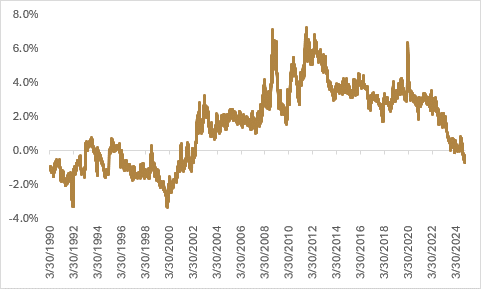

The continued back-up in bond yields leaves multi-asset investors in a precarious position. On the one hand, the potential for widening fiscal deficits and a resurgence in inflation doesn’t paint a rosy fundamental position for bonds. On the other hand, when you look at bond yields relative to earnings yields in the U.S., the “equity risk premium” is now into negative territory. As an investor deciding between buying U.S. equities or U.S. 10-year government bonds today, the price that you are paying to invest in the S&P 500 equates to an expected earnings yield over the next twelve months that is less than the yield on a 10-year government bond. Given that equities are a riskier investment than government bonds, investors generally need to receive a premium to invest in equities over bonds, and a negative equity risk premium is something we haven’t seen in financial markets for over twenty years. However, just because there is a negative equity risk premium doesn’t mean this can’t persist if investors believe the “riskiness” of bonds has increased due a continued deterioration of the fiscal outlook.

From an absolute perspective, U.S. equity valuations are stretched relative to history, but the fundamental outlook for the economy, corporate earnings, and consumer demand would suggest equities are closer to fully valued rather than overvalued. At a price of 24x forward earnings for the S&P 500, we would caution that these lofty valuations have the potential to lead to more reflexive selloffs on troubling economic news, given sentiment is already in jittery territory due to relatively elevated multiples. Equities can generally absorb a gradual shift higher in bond yields without a large selloff; however, sharp spikes can cause consternation for equity investors. Goldman Sachs released a note in November of last year highlighting that equities can run into trouble when bond yields increase by more than two standard deviations over the course of a month. A two standard deviation increase is approximately a 60-basis point rise in yields, and we’ve seen a 50-basis point rise in the U.S. 10-year over the last month.

The back-up in bond yields isn’t just specific to the U.S. market, with fixed income markets around the world having to contend with rising yields. The U.S. is one of the cleaner dirty shirts so to speak, as the yawning fiscal deficit has been somewhat masked by stronger-than-anticipated economic growth. For equity investors, it may feel as if the air is thinning out at these elevated valuation levels, but if a stronger economy is leading to a resurgence in inflation based on firming aggregate demand, equities should be able to continue to do well, while bond markets struggle to keep their head above water.

Europe and the U.K. are in much different positions. The French and British are struggling to pass budgets that will help narrow fiscal deficits, while at the same time facing sluggish economic growth, which has the potential to be made worse if an increase in tariffs results in a tit-for-tat trade war. A stagflationary environment is much more of a possibility in Europe and the U.K. than in the U.S., though the U.S. economy isn’t necessarily out of the woods. The biggest worry for U.S. financial markets—and the broader global economy—is an increasing term premium and bear steepening of the yield curve that tightens financial conditions, which softens the labour market and leads to a decrease in consumer demand. We’re not at the point where Krampus bond vigilantes have increased the term premium enough to slow economic growth, but there could be additional pain if the fiscal deficit continues to be an issue.

We’ve said for some time that the fight for the Fed and other central banks will be around containing a resurgence in inflation, and in the absence of meaningful progression in the narrowing of global government deficits, investors should be analyzing how an allocation to commodities could help improve the risk and return characteristics of portfolios in times where inflation uncertainty remains elevated.

Happy investing!

Scott Smith

Chief Investment Officer

DISCLAIMER:

This blog and its contents are for informational purposes only. Information relating to investment approaches or individual investments should not be construed as advice or endorsement. Any views expressed in this blog were prepared based upon the information available at the time and are subject to change. All information is subject to possible correction. In no event shall Viewpoint Investment Partners Corporation be liable for any damages arising out of, or in any way connected with, the use or inability to use this blog appropriately.