While the initial shock from the April 2nd “Liberation Day” tariff announcement has subsided, markets remain stuck on a rollercoaster of policy uncertainty. Headlines continue to drive intraday volatility as investors try to make sense of shifting trade rules—new tariff categories, exemptions, and delays—all of which muddy the outlook for corporate earnings. Not only are analysts scrambling to adjust their earnings models, but some companies like Delta Air Lines have withdrawn their full-year financial guidance. The pullback in equity prices has enticed investors to “buy the dip” as stocks go on sale; however, the hypothetical bargains could be more expensive than anticipated if corporate earnings see large downward revisions and multiples expand without a meaningful rebound in prices.

Although equity markets have borne the brunt of the volatility, the real alarm bells began to ring when the bond market bucked its traditional safe-haven status and started selling off alongside equities. The synchronized weakness sent a clear message: investors are growing concerned that trade policy missteps may not only dent global growth but could also fuel inflation, leaving the Federal Reserve (Fed) stuck between a rock and a hard place. In the midst of the market selloff, President Donald Trump touted lower oil prices and borrowing costs from the initial reciprocal tariff announcements as a good development for the U.S. economy, so when yields reversed course, this was cause for consternation.

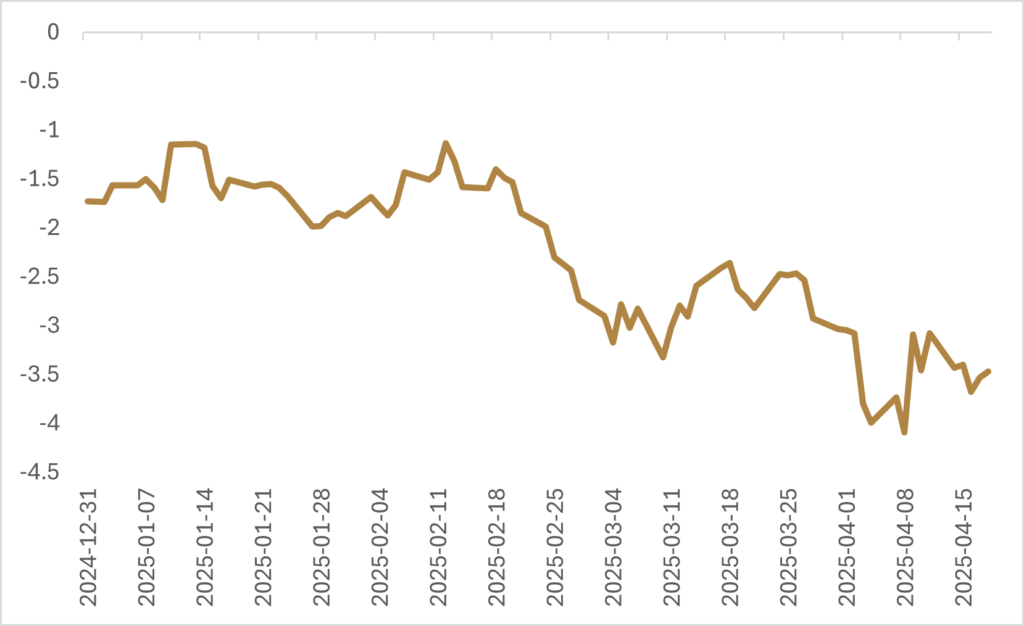

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has been clear that stock prices and Wall Street aren’t the priority—“it’s Main Street’s turn”—but rising yields flew in the face of this narrative. The 10-year U.S. Treasury yield spiked from 4.0% on April 4th to nearly 4.6% a week later, the highest level since Trump’s inauguration. That surge in yields, even as equities were declining, spurred speculation that China was dumping U.S. Treasuries in retaliation. While the narrative of a stealth move by China makes for a compelling headline, there’s yet to be persuasive evidence to support the claim. The U.S. dollar held steady during the selloff and the offshore renminbi weakened—both signs that large-scale liquidation from China was unlikely. Instead, it’s more plausible that the spike in yields came from a wave of de-leveraging as investors sold relatively resilient assets like Treasuries and gold to cover margin calls. A liquidity crunch in financial markets likely exacerbated the pressure on Treasuries, especially for hedge funds caught in a popular trade betting on changes to the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR) rules. These investors had piled into Treasury positions, hoping the U.S. would soon exempt them from capital calculations for banks, lowering trading costs. But as swap spreads began to narrow aggressively early last week, it signaled stress. It wasn’t until April 14th that the Treasury Department reassured markets that SLR reform was still on the agenda—offering some temporary relief to rattled bond investors as swap spreads started to widen again.

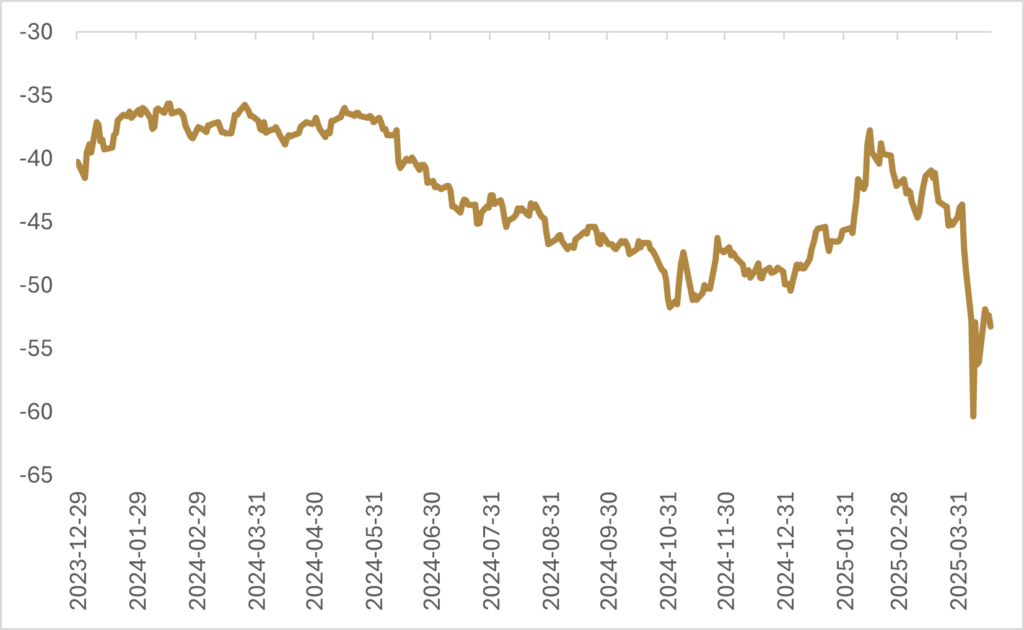

Beyond technical factors, the bigger concern has been the risk of tariffs reigniting inflation expectations. Tariffs don’t necessarily have to be inflationary if they are accompanied by an appreciation in the domestic currency that offsets the impact of the price rise from the tariff. However, the U.S. dollar has been on a declining trajectory all year, which is not the direction you’d like to see if you are of the opinion that tariffs aren’t inflationary. If tariffs do result in a jump in consumer prices because there is no domestic currency appreciation, they can still be viewed as a one-time upward shift in prices—the real issue is whether consumers and businesses see those price increases as transitory or persistent. During the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) press conference in March, Fed Chair Jerome Powell took a similar stance and calmed already anxious markets by describing the expected price impact from tariffs as “transitory”—a word markets hadn’t heard in a while. But in remarks earlier this week, Powell’s tone shifted. He acknowledged that the magnitude of the announced tariffs was larger than anticipated and conceded that the Fed may face a tough balancing act between curbing inflation and supporting employment, signaling to markets that the Fed is growing concerned that a stagflationary environment may be on the horizon. Powell indicated that the Fed must be certain that a tariff-driven jump in prices doesn’t feed into longer-run inflation, a potential challenge to the market view that the Fed will cut interest rates three to four times in 2025. The summary of economic projections at the March FOMC meeting showed the median member anticipated two interest cuts in 2025, but there was a hawkish skew to the distribution with eight members expecting only one or no cuts. The gap between market expectations and Fed guidance is growing—and with it, so is volatility in the bond market.

Going forward, markets will remain highly sensitive to fiscal and monetary policy shifts. For now, it appears the administration’s tolerance for rising yields is lower than its tolerance for falling equities. So far, initiatives to cut spending and reduce borrowing costs have not yielded much, and with the risk of a recession on the horizon—along with potential bailout packages for impacted industries—markets are starting to question if fiscal discipline is achievable. On top of that, Powell’s insistence to wait for greater clarity on how consumer prices and inflation expectations will be impacted by tariffs before adjusting monetary policy has drawn Trump’s ire, raising the risk that the Fed Chair could be replaced. The U.S. 10-year term premium—the extra yield investors demand for holding a long-term bond instead of rolling over short-term bonds—is back to the highs of the year. If the executive branch of the U.S. administration continues to signal to markets that the Fed’s independence is under threat, we’d likely see a continued rise in long-term yields as the term premium widens out further due to continued policy uncertainty and ongoing inflation fears.

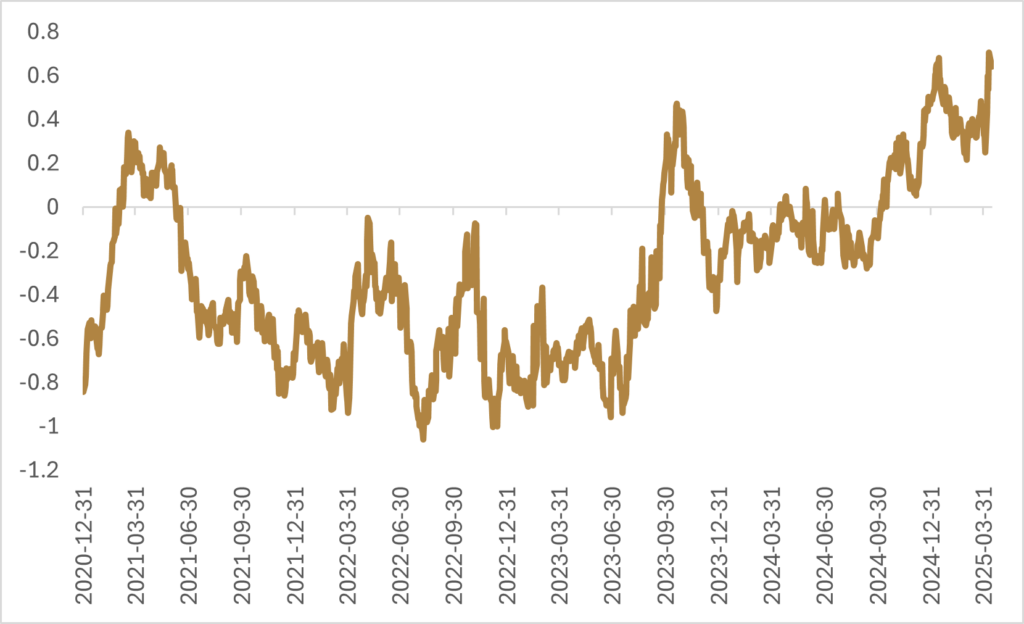

Even if the Fed does lower short-term interest rates, it may not translate into lower long-term borrowing costs if markets believe looser monetary policy will simply stoke inflation. Add to that the long-term implications of a more isolationist U.S. trade policy, and you begin to see how foreign demand for U.S. Treasuries could wane. Countries with smaller trade surpluses with the U.S. will have fewer U.S. dollars to recycle into Treasuries, and over time, we may see a slow but steady diversification away from the U.S. dollar. Europe and Asia—especially countries like Germany and Japan—could benefit if they increase debt issuance to support expanded trade with each other, independent of the U.S. That, in turn, would create stronger demand for non-dollar assets and potentially trigger a multi-year reallocation of global capital.

The intersection of trade, inflation, and central bank independence has put the bond market in the driver’s seat. While equity markets may be grabbing the headlines, it’s the movement in yields—and what they imply about long-term policy credibility—that investors should be watching closely. While the path forward is anything but clear, signs may be pointing to a transition away from U.S. exceptionalism. If a more isolationist approach from the U.S. continues, we would opine that global diversification should be a prominent feature of investment portfolios to create a more resilient framework for navigating volatility and policy uncertainty. Commodities remain a key strategic asset class in this context, particularly as they tend to outperform in environments characterized by elevated inflation and fractured geopolitical alliances.

Happy investing!

Scott Smith

Chief Investment Officer

DISCLAIMER:

This blog and its contents are for informational purposes only. Information relating to investment approaches or individual investments should not be construed as advice or endorsement. Any views expressed in this blog were prepared based upon the information available at the time and are subject to change. All information is subject to possible correction. In no event shall Viewpoint Investment Partners Corporation be liable for any damages arising out of, or in any way connected with, the use or inability to use this blog appropriately.