Financial markets love clean narratives, but geopolitical developments rarely deliver them. The U.S. capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro over the weekend was a headline shock, yet the most likely commodity-market outcome is near-term ambiguity with messier second-order implications. The bigger takeaway is that, in an era of multipolarity and a U.S. refocus on the Western Hemisphere, commodities remain a linchpin of supply-chain security in a more fractured world order.

The rationale narrative for Maduro’s capture is relatively straightforward: access to oil resources and a reassertion of U.S. influence in the Western Hemisphere by removing a socialist regime openly hostile to Washington. The drug charges provide useful cover, but they are unlikely to be the primary driver of the regime-change calculus—particularly after the U.S. recently pardoned former Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández, who had been convicted and sentenced to 45 years for trafficking cocaine into the U.S.

The near-term global oil-market consequences are unlikely to be earth-shattering. We should expect a geopolitical premium to remain embedded until there is clarity on whether the post-Maduro governing apparatus, now led by Vice President Delcy Rodríguez, chooses confrontation or cooperation with U.S. goals to stabilize the country and rebuild oil infrastructure. Rodríguez’s messaging has already flip-flopped, moving from hostile rhetoric to calls for a “cooperating agenda.”

The operation has echoes of Panama in 1989–90, when the U.S. captured Noriega on drug charges and extradited him to the U.S., but the Venezuela operation has important nuances. Panama had an opposition government sworn in immediately, while Venezuela lacks a clear, widely accepted transition path, despite figures such as María Corina Machado and Edmundo González. In that sense, this looks more like “regime-change lite,” with potential continuity of the regime rather than a clean reset. Our base case is not a second phase of military action or “boots on the ground,” but the tail risk is that a non-cooperative Caracas draws a more forceful U.S. posture, raising the probability of sanctions escalation and operational disruption. Markets appear to be underpricing that risk by anchoring to a simple story in which a U.S.-friendly outcome quickly unlocks a wave of new barrels hitting the market.

Where the weekend operation matters more is the medium-term setup. We have been bearish oil in the near term because the market is working through a glut from non-OPEC supply growth alongside a gradual unwind of some OPEC+ voluntary cuts, while the medium-term thesis has been that chronic underinvestment tightens balances two to three years out. Venezuela introduces a new variable, as the prospect of U.S. capital and sanctions relief could pull incremental supply back online over time. The story for global oil markets is not “new barrels tomorrow,” but rather the potential for meaningful Venezuelan production gains over a multi-year horizon if the transition stabilizes and contracts become investable.

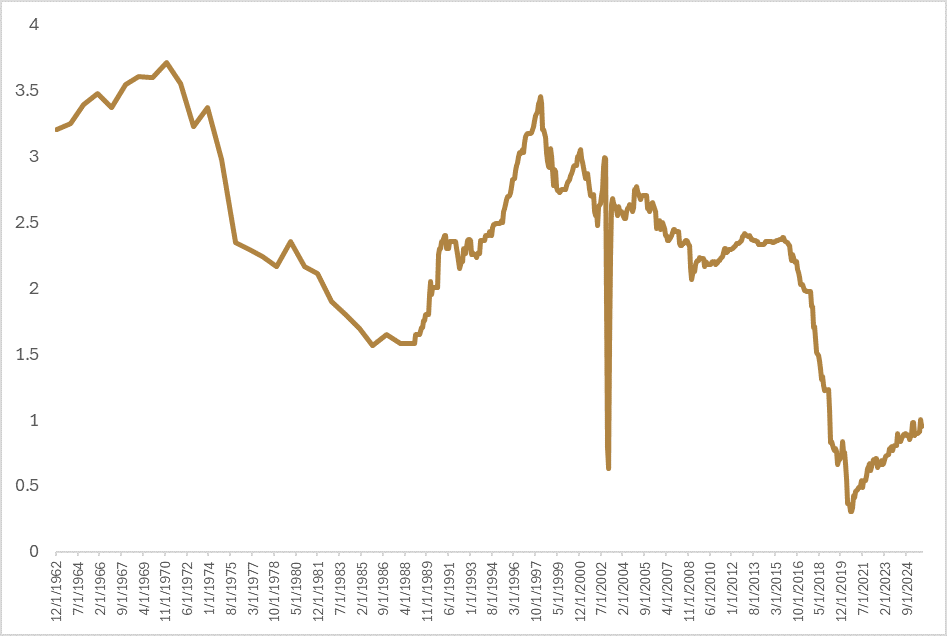

Venezuela is currently producing roughly 0.8–0.9 million barrels per day (mb/d), versus a peak near 3.5 mb/d in the 1970s, after which capacity was eroded through mismanagement and underinvestment. A credible incremental +1.0 mb/d likely takes three to seven years even in a constructive scenario, and it requires substantial reinvestment in diluent logistics, upgrading, power reliability, and field maintenance. With Brent near US$60 per barrel and Venezuelan Merey priced at roughly a US$20 per barrel discount to Brent, the economics do not yet scream “rush in,” particularly given political uncertainty. Over time, if sanctions ease and stability improves, that discount could compress and the investment calculus improve—but this is not an overnight story. A more credible near-term angle is oil production in Guyana, where reduced perceived risk around Venezuelan territorial pressure could lower the regional geopolitical premium, even if Guyana’s production ramp was likely to proceed regardless.

For Canada, the concern that Venezuelan heavy could compete with Canadian barrels is credible—but nuanced. A sustained re-entry of Merey into the U.S. Gulf Coast would likely pressure heavy differentials, as the Gulf is a key marginal outlet that helps clear Western Canadian supply. However, a full-scale displacement narrative runs into two constraints: Venezuela would need to ramp far beyond today’s output, and the U.S. would need additional infrastructure to move incremental imported heavy from the Gulf into Midwest refining centres. Today, roughly 0.7 mb/d of Canadian crude flows to the Gulf (about 20% of Canadian exports to the U.S.), while approximately 2.5 mb/d goes to the Midwest (just over 60%). That means competition risk is most acute in the Gulf first, with the Midwest harder to displace quickly without meaningful logistics changes. Mid-Valley is one of the few northbound options from the Gulf into parts of PADD 2, but its capacity is only about 240 kb/d, and Merey would likely require blending or upgrading to meet pipeline specifications.

Our base case is partial displacement for Canadian crude in the short term. Venezuelan barrels compete in the Gulf, but they also displace other heavy sources such as Mexico and Colombia, while the market could re-balance some Canadian volumes via TMX utilization. In that scenario, the near-term effect of renewed U.S. imports of Merey is a modest widening in the WCS differential. The stress case is a sustained Venezuelan flow that materially replaces Canadian barrels into the Gulf without an equal-and-opposite expansion in Canadian egress. In that world, the clearing mechanism is congestion in Western Canada, and WCS could gap meaningfully wider. That is why additional Canadian market access—particularly to Asia—remains strategically important: it diversifies demand, reduces vulnerability to competition-driven dislocations, and lowers the risk that a single geopolitical event can reprice Canadian barrels overnight.

The near-term winners from the weekend’s operation are U.S.-aligned Latin American governments that benefit from a perceived increase in regional stability. In a recent note, we highlighted Chile as a potential beneficiary of a policy pivot toward resource development under a Kast-led government; improved stability could also ease migration pressures, giving Santiago political breathing room to refocus on growth and permitting. The near-term losers, beyond Canada’s heavy-differential sensitivity, are governments in the hemisphere that are openly at odds with Washington. Colombia has drawn Trump’s ire amid a sharp disagreement on counter-narcotics and security policy, but Cuba is the more obvious flashpoint under a renewed “Monroe Doctrine” posture. Cuba is a one-party communist state experiencing acute stress from power fragility, shortages, and sporadic protests. While the bar for direct intervention is far higher than in Venezuela, increased U.S. pressure could test regime cohesion at the margin. Separately, Cuba’s strategic mineral endowment—particularly nickel and cobalt (roughly 6% and 7% of global reserves, respectively)—adds a supply-chain dimension to how Washington might frame its interests.

The longer-term question for any “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine is durability. A “big stick” can create wins in the short run, but sustaining influence requires economic gravity. China remains deeply intertwined with Latin America, often as the largest trading partner for major commodity exporters such as Brazil, Chile, and Peru, with relationships anchored in raw materials. For the U.S. to deepen hemispheric influence, it would need to import more regional commodities and expand its own manufacturing and processing footprint. That is not an easy fit given labour constraints, which is where Mexico’s industrial base—or a step-change in U.S. automation and robotics—becomes strategically relevant. Over time, Washington may need to tilt back toward Roosevelt’s original framing of the Monroe Doctrine corollary: “speak softly and carry a big stick,” pairing credible deterrence with a compelling economic alternative.

What is clear is that a renewed U.S. focus on the Western Hemisphere under the Monroe Doctrine does not reduce commodity risk—it reprices it. In a multipolar world, influence is increasingly measured by who can secure raw materials, who controls the logistics to move them, and who can offer stable, rule-of-law supply chains when shocks hit. If Washington is serious about consolidating hemispheric leverage, it will lean harder on the region’s comparative advantage—energy, metals, and agricultural inputs—making commodities both a strategic asset and a geopolitical bargaining chip. For investors, the implication is straightforward: commodities are no longer just a cyclical trade tied to growth and inflation; they are becoming a structural pillar of resilience as supply chains re-regionalize, alliances harden, and the “security premium” embedded in real assets becomes more persistent.

Happy Investing!

Scott Smith

Chief Investment Officer

DISCLAIMER:

This blog and its contents are for informational purposes only. Information relating to investment approaches or individual investments should not be construed as advice or endorsement. Any views expressed in this blog were prepared based upon the information available at the time and are subject to change. All information is subject to possible correction. In no event shall Viewpoint Investment Partners Corporation be liable for any damages arising out of, or in any way connected with, the use or inability to use this blog appropriately.