Equities paused last week as investors questioned whether the AI capital-expenditure (capex) boom is sustainable and whether future earnings justify the vast build-out. Emerging vendor-financing loops in mega-cap tech—think Nvidia investing in OpenAI, OpenAI inking a cloud deal with Oracle, and Oracle then using proceeds to buy Nvidia chips—have raised cautionary flags and revived 2000s-era bubble analogies. While incumbents’ gains rest on solid earnings and strong balance sheets, companies like Meta and Oracle have recently tapped the bond market for roughly $48 billion to fund infrastructure projects, sharpening scepticism about when investor payoffs will arrive. Comments from OpenAI’s CFO floating a potential government backstop for chip-fab financing—since walked back—added to worries about capex sustainability and “too-big-to-fail” dynamics. The broader risk to the AI narrative is straightforward: a massive infrastructure push that overshoots, echoing the railroad overbuild of the late 1800s.

Think of today’s AI build-out as a steam-engine moment: a general-purpose technology that unlocks new production functions and sparks an investment race in the rails that carry it. In the 19th century, capital poured into track, rolling stock, depots, and feeder industries (steel, coal, land syndicates). The result was transformative capacity and lower marginal transport costs—but also classic boom-bust dynamics: overlapping routes, thin last-mile economics, speculative finance, and periodic washouts before durable winners emerged.

AI has a similar vibe. Today’s “rails” are data centres, power generation and grid upgrades, advanced chips, cooling, fibre, and software stacks. Scale can push unit costs down, but exuberance risks overbuilding in the wrong places. Early leaders can still win—yet returns may drift toward firms that build productive layers on top of the infrastructure—much as transportation companies captured gains from cheaper rail transport in the late 1800s. The counterpoint: digital assets scale far better than rail rights-of-way, and network effects can concentrate value more than railroads ever did. Meanwhile, despite some off-balance-sheet flags, mega-cap tech still boasts strong balance sheets and highly profitable cloud and advertising engines generating cash flows sufficient to fund the recent capex explosion.

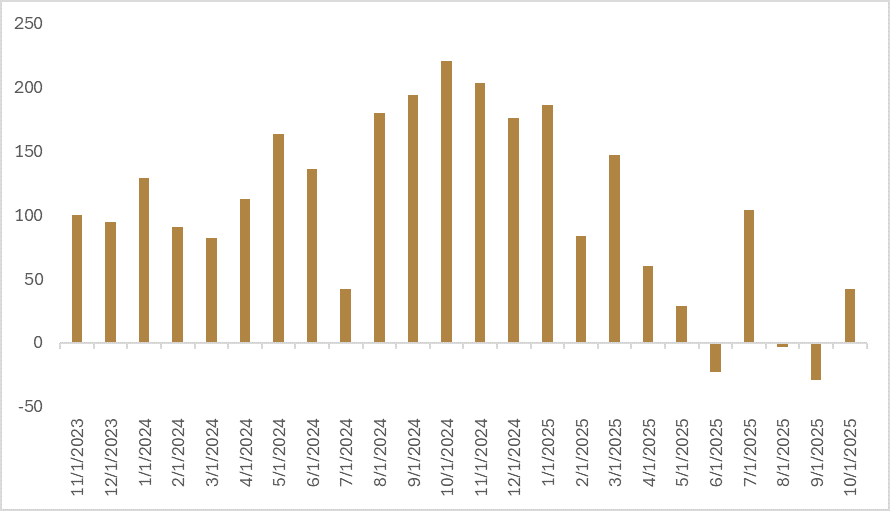

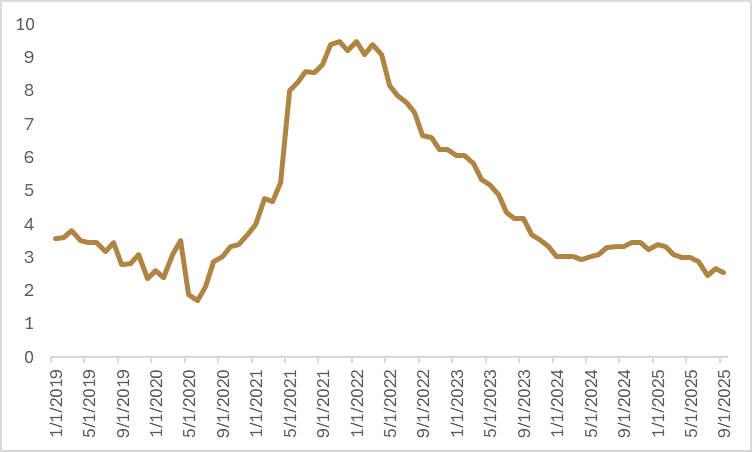

The mega-cap surge—and the sense that AI is “eating the world”—sits alongside a K-shaped economy. GDP and corporate earnings look solid, but consumer sentiment is weak as a softening labour market heightens affordability worries. With official data flow patchy due to the government shutdown, outplacement firm Challenger reported roughly 150,000 announced layoffs in October—the most for an October since 2003, concentrated in warehousing and technology—with “cost-cutting” and “artificial intelligence” cited as top reasons. Against that, firms announced approximately 283,000 planned hires, but these are largely in the tech space. On the flip side, ADP showed private payrolls increasing by 42,000 in October (above economists’ expectations) yet noted that pay growth has been flat for over a year, consistent with the downbeat sentiment. As we’ve flagged, this K-shape is politically awkward: it raises the incentive for the administration to support the bottom leg and to “run it hot” into the 2026 midterms.

While the AI-fuelled rally and a soft labour market dominated headlines, a quieter—but market-relevant—story was the Supreme Court’s review of the administration’s use of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) to levy sweeping tariffs. This is more than a constitutional skirmish: it’s arguably the marquee macro case of the fall sitting because it tests a key pillar of the current trade regime. Lower courts have already rejected the IEEPA tariff move, and after this week’s arguments, the justices look unlikely to reverse the lower court’s ruling. The government leaned on “emergencies” — such as trade deficits and fentanyl — to justify action under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), a 1977 law granting the president authority to regulate commerce in response to unusual and extraordinary foreign threats. However, conservative justices — led by Neil Gorsuch — questioned this interpretation, emphasizing that the IEEPA’s text is limited to sanctions and embargoes, not the imposition of broad, revenue-raising tariffs. Several justices also flagged the major-questions doctrine—actions of “vast economic and political significance” require clear congressional authorization—the same doctrine the Court used in Biden v. Nebraska to strike down mass student-loan forgiveness. With tariffs projected to raise approximately $2.6 trillion over 10 years, the “major” threshold seems plainly implicated. Gorsuch also added a separation-of-powers concern: if Congress can hand the Executive sweeping tariff authority, where does the delegation stop—and how would Congress ever claw it back? He even floated a climate-emergency hypothetical in which a future president could impose steep tariffs on gasoline-powered cars—underscoring the breadth of power at stake.

Market odds moved fast: Polymarket probabilities of the Court upholding Trump-era tariffs cratered after the conservative justices’ skeptical questioning. Typically, fall arguments yield decisions between January and late June of the next year, but the administration has asked for an expedited ruling, so a faster timeline is possible. A broad loss for the administration could trigger more than $100 billion in refunds and, per Bloomberg Economics, push the average effective tariff rate down to approximately 6.5 per cent—a level last seen before the “Liberation Day” announcements. That would be fiscally stimulative and supportive for risk appetite, but it likely pressures long-end yields as tariff refunds widen the deficit. Even so, contingencies remain. The White House could invoke a never-used Trade Act of 1974 provision allowing up to 15 per cent tariffs for 150 days to address trade imbalances, or it could seek explicit congressional authorization to re-establish parts of the current regime.

It’s hard to see Congress authorizing sweeping tariffs now. The Senate recently voted to overturn tariffs on Brazil and Canada (measures unlikely to clear the House—and potentially moot if IEEPA tariffs are rolled back). At the same time, Democrats notched their strongest off-year wins since 2024, with gubernatorial victories built around an economic-affordability message. As we’ve noted, the economy, trade, and inflation are the administration’s weakest polling lanes. Last week’s results were a shot across the bow on what voters want addressed heading into the 2026 midterms. Net-net, incentives line up for tariffs and trade salience to fade in favour of near-term affordability: easing consumer-price pressure where possible or using tariff rebates to blunt the K-shaped squeeze on households.

With trade policy likely to turn less hawkish, a still-accommodative Fed (even if a December cut isn’t a lock), and visible measures to ease affordability at the lower leg of the K-shape, the macro backdrop remains broadly supportive for risk assets. But concentration risk in mega-cap tech, the rise of off-balance-sheet structures, and vendor-financing loops argue for discipline in investment portfolios. Technology names will continue to be vital to the broader economy, though investor portfolios could benefit from rebalancing some growth holdings into more defensive names with a quality and/or value tilt. Commodities should continue to play a pivotal role in portfolio construction—especially those that benefit from AI-capex spend without adding tech-specific concentration. On the rates side, assume a sticky term premium as deficits re-widen—keep duration tactical, using it as a shock absorber if the labour market rolls over more sharply. The aim is multi-asset portfolio construction that harnesses diversified sources of carry and cash flow, balances factor risk, and calibrates position sizes by volatility—so the portfolio can compound through policy swings rather than react to them.

Happy investing!

Scott Smith

Chief Investment Officer

DISCLAIMER:

This blog and its contents are for informational purposes only. Information relating to investment approaches or individual investments should not be construed as advice or endorsement. Any views expressed in this blog were prepared based upon the information available at the time and are subject to change. All information is subject to possible correction. In no event shall Viewpoint Investment Partners Corporation be liable for any damages arising out of, or in any way connected with, the use or inability to use this blog appropriately.